Is panel attrition the same as nonresponse?

All of my research is focused on the methods of assembling and analysis of panel survey data. One of the primary problems of panel survey projects is attrition or drop-out. Over the course of a panel survey, many respondents decide to no longer participate.

Last july I visited the panel survey methods workshop in Melbourne, at which we had extensive discussions about panel attrition. How to study it, what the consequences are (bias) for survey estimates, and how to prevent it from happening altogether.

These questions have a lot in common with the questions that are being discussed at another workshop for survey methodologists: the nonresponse workshop. The only difference is that at the nonresponse workshop we discuss one-off, cross-sectional surveys, and at the panel survey workshop, we dicuss what happens after the first wave of data collection.

I am in the middle of writing a book chapter (with Annette Scherpenzeel and Marcel Das of Centerdata) on attrition in the LISS Internet panel, and one of the questions that we try to answers is whether nonrespondents in the first wave are actually similar to respondents who drop out at wave 2 or later. Or to be more precise, whether nonrespondents are actually similar to fast attriters, or to other sub-groups of attriters.

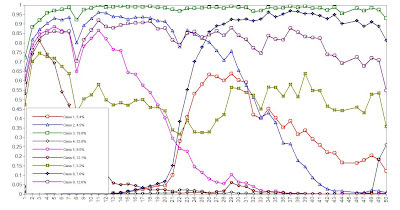

The graph below shows attrition patterns for the people in the LISS panel for the 50 waves that we analysed. The green line on top represents people who have response propensities close to 1, meaning they always participate. The brown line represents fast attriters, and the pink, dark blue, and purple lines slowers groups that drop out more slowly. You also find new panel entrants (dark grey and red line), and finally, a almost invisible black line that has response propensities of 0, meaning that although these people consented to become a panel member, they never actually participate in the panel.

Click on the Figure to enlarge

For the whole story you’ll have to wait for book on ‘Internet panel surveys’ to come out somewhere in 2013, but I’ll focus here on comparing initial nonrespondents to respondents who do consent, but then never participate.

These groups turn out to be different. Not just a little different, but hugely different. This was somewhat surprising to me, as many survey methodologists believe that early panel attrition is some kind of continuation of initial nonresponse. It turns out not to be. Fast attriters are very different from initial nonrespondents. My hypothesis for this is that some specific groups of people may ‘accidentally’ say yes to a first survey request, but then try to get out of the survey as fast as they can. I am still not sure what this implies for panel research (comments very welcome): does it mean that the methods that we use to target nonrespondents (persuasion principles of Cialdini et al. 1991) might not work in panel surveys, and that we need to use different methods?

I think the first few waves of a panel study are extremely important for keeping attrition low in the long run. So, I think we should perhaps prolong some of the efforts that we use in the recruitment phase (advance letters, mixed-mode contact strategy), in the first waves as well, only to resort to a cheaper contact mode later, once panel members have developed a habit of responding to the different waves in a panel.